No Place Like Homestay

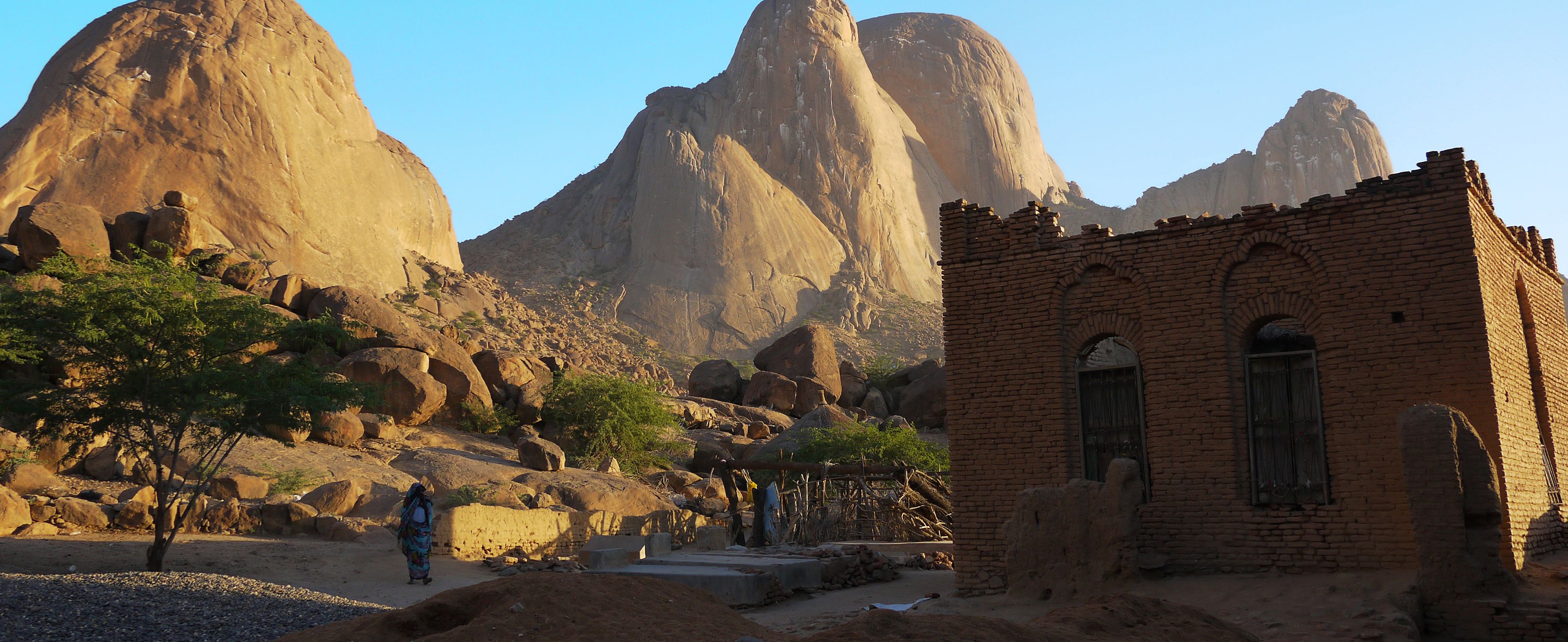

Mahasin Ismail was inspired to tackle the issue of Sudan’s underserved tourism sector in her native country. She launched a digital marketplace for hosted accommodations, an innovative solution that’s using inclusive tourism as a vehicle for change.

While completing a leadership program in Texas, 18-year-old Mahasin Ismail had a life-changing experience with a local family that transformed her notion of what home means. Once she returned to her native Sudan she launched Saunders Homestay, a digital platform that helps local families host travellers for short stays in their own homes. Named after her Texan host family, the company provides income to struggling families, training opportunities to Sudanese youth, and community-based tourism that’s focused on creating lasting cultural connections.

How did you come up with the idea of Saunders Homestay?

After leaving Texas, I continued a relationship with my host family but couldn’t stop thinking about what makes a home. What makes people feel most at home? Is it a physical place, or a feeling? I realized that home is a fragmented dream that we dare remember. It’s a fleeting memory that arrives unexpectedly, and your family can be biological or chosen. I decided to honour my experience with the Saunders family and launched Saunders Homestay with a few of my friends. I believe everyone deserves to have deep and memorable travel experiences, discover new faces, not empty places, and connect with locals through a cultural exchange. The heart and soul of Sudan is secretly locked inside the smiles of its people. Their generosity, hospitality, and stories need to be voiced to the world in order to combat the stereotypes about Sudan in the media.

You are such an inspiration. When it comes to your company, who inspires you?

One of my biggest role models is Brian Chesky, the co-founder of Airbnb—Saunders Homestay is similar to his business model. Closer to home is 249Startups, an entrepreneurial ecosystem that is doing great things with limited resources for grassroots innovators in Sudan. Last February, they offered financial management, inclusion, and business training sessions to young girls.

What potential did you see in targeting Sudan’s tourism sector?

Tourism isn’t only regarded as a potentially important economic source in Sudan; it can also be an essential tool to promote mutual understanding, peaceful dialogue, and tolerance between the host community and visitors. Unfortunately, the homestay sector is marginalized in Sudan, left behind in the oligopoly competition between a few private hotels. Omderman, a city inside the capital Khartoum, where I live, is recommended by visitors, but we only have three hotels. I wanted to target an area that could provide opportunities to the public and private sectors, and reduce unemployment. My goal was to develop a new solution that was sustainable, contemporary, and inexpensive, with a marketing advantage—a digital marketplace where the hard currency could go to civilians and raise their standard of living. I didn’t want to make rich hoteliers richer. It was also a chance for young people to find employment by training them to be tour guides. The power of this business model is that we’re implementing the soul of independent entrepreneurship in Sudanese society. Everyone can be an entrepreneur.

What were some of the challenges you faced when you launched the project?

Starting a company with a group of young friends between the ages of 17 and 20 with no previous business experience meant we had to educate ourselves quickly... But the biggest challenge was overcoming stereotypes and gaining acceptance. In my conservative Islamic community, the idea of hosting a complete stranger who would mix with wives, sisters or daughters almost seemed impossible. Even my own mother refused at the beginning! I hosted the first pilot stays in my own home with resistance from my family. I remember one couple from Belgium and Portugal who stayed with us for five days, and in the end, even my mother was delighted. We transformed the guest experience from “visit it” to “live it.” Everything from Sudan’s power outages to meeting people in the street to a visit from the milkman are things tourists would never experience otherwise.

How did your business model change after the pandemic?

To date, we don’t have any investors, so when COVID-19 hit, all startups, along with the tourism sector, suffered. The travel restrictions meant zero guests were coming to Sudan, and the business almost stopped. My team came up with an idea that could reactivate our company while focusing on social enterprise. We launched #hostahero, hosting healthcare and frontline workers for free. I remember a Chinese traveller who arrived in Sudan via Ethiopia and none of the hotels would host him because of the stigma associated with the pandemic. I heard that he had slept in the street one night—it wasn’t right. One of our host families took him in for two weeks, and they taught each other how to make traditional recipes. It’s stories like these that show the world how we can break down stereotypes.

What advice can you give others who want to be the change they see in the world?

Believe in yourself. You have a voice and it matters. You can activate change in your geographic area with limited resources. Don’t wait for external funding. Identify problems and come up with solutions.